Exhibit

Opening May 4, 2017 at the Musée national d'art moderne, level 5

A new dossier exhibition on the relationship between art and music will be on display in the permanent collection.

L'œil écoute

Once a year a new sequence of dossier exhibitions set among the display of the permanent collection offers visitors a fresh glance at the history of 20th-century art by focusing on a specific theme. Occupying vitrines, passages and rooms, these study displays cast light on hidden aspects of modern art: after a sequence devoted to the great communicators, the historians, critics and enlightened art-lovers who contributed so much to writing its history, and another devoted to the politics of art, looking at artists’ engagement with the great ideologies of the 20th century, the museum today highlights the connections that existed between music and the visual arts from 1905 to the mid-1960s.

Once a year a new sequence of dossier exhibitions set among the display of the permanent collection offers visitors a fresh glance at the history of 20th-century art by focusing on a specific theme. Occupying vitrines, passages and rooms, these study displays cast light on hidden aspects of modern art: after a sequence devoted to the great communicators, the historians, critics and enlightened art-lovers who contributed so much to writing its history, and another devoted to the politics of art, looking at artists’ engagement with the great ideologies of the 20th century, the museum today highlights the connections that existed between music and the visual arts from 1905 to the mid-1960s.

Entitled “L’Œil écoute” – perhaps best rendered as “the listening ear” – this new byway winding among the founding figures and major movements of modern art takes its title from Paul Claudel’s book of the same name, published in 1946, in which the writer set himself to “listen” to a number of different paintings, among them Rembrandt’s La Ronde de nuit and Watteau’s L’Indifférent. Visitors to the Museum are thus invited to lend their eyes and ears to the Parisian nightlife that – from Montmartre to Montparnasse, from Bal Bullier to Bal Tabarin, from fancy-dress ball to Bal Banal, from Josephine Baker to the Black Birds – so enchanted modern artists and their musical colleagues, with its glittering shows and the creative spur of costumes, movements, dances and musical numbers.

The ballet, which enabled creative artists (responsible for sets, costumes, choreography and music) to unite their efforts, was emblematic of a modernism that was keen to abolish boundaries between the arts and dreamt of the total work of art. One sees this in the displays devoted to the Ballets Russes, notably featuring costumes designed by painters Mikhail Larionov and Natalia Goncharova for Stravinsky, to the Ballets Suédois, and to that remarkable French composer, Erik Satie, who gathered many artists around him: Picasso, for the ballet Parade, and Braque, Brancusi and Picabia. Not so personally close to Satie, Marcel Duchamp evidently shared much of the same attitude of humour and artistic self-mockery, exemplified in ready-mades and “furnishing music.”

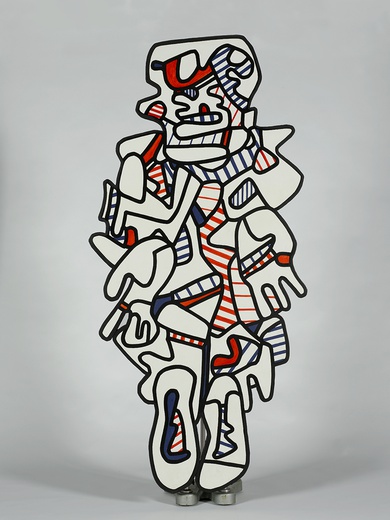

There were theoretical links between music and the visual arts as well. In the 1910s, music served as a model to negotiate the transition between figuration and abstraction. In painting, artists such as Vassily Kandinsky, Léopold Survage and František Kupka rejected figuration for an art which – like music – would free itself of the burden of representation, a painting that mobilised rhythm, colour and modulation to touch the emotions. In April 1932, Henry Valensi sought to give institutional form to these researches in founding the Association of Musicalist Painters. These could be recognised by “works that remain independent of each other, save that they be influenced by music.” In another register, Jean Dubuffet in the post-War years developed the same interest in music, rendering it in painting and making music himself.

“I recommended to the visitor of museums to open their ears like their eyes, because sight is the organ of active approval, of intellectual conquest, while the hearing is that of the receptiveness.” Paul Claudel, Œuvres en prose, Paris, 1965

In other cases, experiment in the visual arts led to discoveries in the field of music. The American composer John Cage’s reverence for Marcel Duchamp affords a good example. Like Duchamp, whose “beauty of indifference” explicitly derived from the contingent, Cage opened music up to “everything that happens”. While Duchamp produced his Erratum musical, converted chance into form in his 3 Stoppages-Étalon, and introduced everyday life into art with his ready-mades, Cage made chance a method in his musical, literary and graphic compositions. The combined influence of Duchamp and Cage made itself very strongly felt in the 1950s, when some of the composer’s pupils created the “happening” on the one hand and founded the Fluxus movement on the other. This was a period of great permeability between artistic disciplines. While big festivals brought together artists and musicians, from Fluxus to Stockhausen, sound poetry emerged in Europe around such figure as Bernard Heidsieck and Henri Chopin, who discovered the possibilities of the tape-recorder. This overlap took on particular significance with the growing importance of “notation” in the arts. This is the subject of a display of its own at the end, which reveals how notation stands as a hinge between the two disciplines. While musical scores moved away from the traditional note and stave to a freer graphic expression that left greater scope for interpretation, the proto-conceptual artist George Brecht, a pupil of Cage’s at the New School for Social Research, scored “events” on small cards, inviting all-comers to perform them. He opened the way for the conceptual tradition, which – from Lawrence Weiner to Sol LeWitt – made great use of notation.

By Nicolas Liucci-Goutnikov, Curator, Musée national d'art moderne